When political issues bleed into the workplace

This problem was harder than I initially realized. To do justice to the complexity, I’ve split the topics into two parts, first framing the problem and then proposing a solution. In this edition, I map the social and organizational evolutions that enabled political crises in tech companies and demonstrate how such crises unfold within them. In the following edition, I will offer a governance framework that can enable companies (both progressive and traditional) to survive and thrive in the next waves of political crises. Thank you for reading!

HPP#2: How social currents became tech workplace crises

Tech firms have long sought to be apolitical. They perceived themselves as building a neutral infrastructure that would empower society, unfettered by outdated politics, and as having stronger shared identities than partisan divisions could break. The libertarian aspect of old California and the progressive universalism of new California made politics seem like an East Coast phenomenon, remote from where the internet was being shaped for the world.

This illusion has evaporated over the last five years as societal and political issues have broken into the workplace, creating crises. The mechanics of employee activism and corporate response may have contributed to movements’ aims (BLM, Russia-Ukraine, Israel-Gaza), but they have also reduced trust, unity, and speed within many firms. Most recently, it is striking that in many firms, both pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian employees feel their sense of belonging was undermined. As in an early democracy, majoritarian dynamics around issues have led to broken operating norms and undermining the rights of minorities.

Politics is hard. When interviewing founders and people leaders about their most complex people problems, dealing with political crises at work regularly tops the list. The challenge is simultaneously practical and ethical, intimately personal and systemic, driven by deep meaning and base fear. For tech companies, which consider their shared identity, purpose, and collaborative spirit “in their DNA,” political crises can feel existential.

This edition will delve into the genesis of this challenge, tracing the roots back to the Agile methodology and the emergence of Workplace Humanization. I will give a brief history of political crises in tech, explain what factors determine if and where they will strike, and show the limitations of the current practice for managing such crises. The following edition will propose a better solution for managing crises: a cultural governance framework to sustain and evolve companies of various political orientations.

With the cultural zeitgeist shifting away from progressive activism, one could assume that the wave of political crises at work is over. However, with the strong likelihood of a second Trump term or a highly contentious election, we may be in the eye of the storm. Now is the time to learn lessons from our past practice and prepare our organizations for the coming economic, social, AI-based, and geopolitical challenges.

THE RISE OF EMPLOYEE AGENCY

There has been a 30-year trend of increasing expectations for employee agency- the capacity for employees to act independently, make decisions, and exert influence within their roles. The shift towards Agile methodologies was a significant factor in this, creating expectations that employees would self-organize much of their work and that the organization would continuously iterate with employee feedback. The Agile methodology doesn’t set limits on this feedback nor consider that employees would respond to political crises, enforce dominant group norms, or seek to change power dynamics. As a set of workflow principles raised to organizational theory, it’s unsurprising that our political spirits are outside its scope.

The second factor driving the rise of employee agency is the rise of Workplace Humanization (WH). WH weaved together currents from Positive Psychology, the DEI movement, and the War for Talent to expand the role of employees in the workplace and what they expected from their employers. WH advocates see traditional styles as transactional or reductive and to be replaced with empathetic and holistic ones. The core principles of WH directly tie to increased employee agency.

Encouraging authenticity, or “bring your whole self to work,” empowers employees to influence and influence from alternative perspectives.

Offering alignment with individual purpose and values encourages employees to be highly sensitive to their meaning and values being met and drive change or resistance around that.

Creating a sense of belonging and community connection and mobilizing them into groups of like-minded and empowered actors.

There is a recent countertrend against WH: traditionalists who want to return greater power to leadership and have employees leave their personal needs and preferences outside of work. They propose a simple solution to the crisis challenge: “no politics at work,” which effectively bans personal or political discourse on controversial topics in the workplace. As straightforward as it sounds, defining “political” is not a bright-line rule and will be shaped by the leader's political views and perceptions of organizational needs. While it will continue to be a workable model for a subset of tech firms (especially those without significant US offices or in Conservative industries), the cultural trends I outline indicate this model will engage a decreasing share of the talent market. Given the central reliance on talent, most Western tech companies stand to gain more by adapting to the new era of employee empowerment rather than resisting it.

“The core values of the generation are reflected in their prioritizing social activism more than previous generations and in the importance they place on working at organizations whose values align with their own, with 77% of respondents saying that it’s important. Gen Z no longer forms opinions of a company solely based on the quality of their products/services but also now on their ethics, practices and social impact.”

Deloitte, Understanding Generation Z in the workplace, September 2022

While it’s easy to dismiss narratives of generational changes as clickbait, some profound truths underpin them. Culture changes over time, and this change occurs mainly in the formative minds of the young. We commonly see our grandparents' generation as more dedicated, open to hierarchies, and less expressive of personal needs. This observation is supported by academic research on 340k individuals across 100 countries, suggesting newer generations are “more individualistic, more indulgent/less restrained, and less hierarchical.” These cross-cultural changes led to the rise of Workplace Humanization and suggest it will continue to expand.

Writing this piece made me realize I had inaccurate assumptions about Workplace Humanization.

I thought the phenomenon was created by employee marketing, but it’s much more likely that marketing is adapting to a shift in employee preferences.

I assumed WH was rooted in political ideology, as the representing organizations skewed left, but I now think it’s an underlying cultural shift that has carried a relatively obscure philosophy (intersectionality) into prominence.

I thought the WH shift would be temporary. However, WH will likely stay, and thus, the standard organizational model must be updated.

In summary, Agile increases employees’ expectations of their sphere of influence, and Workplace Humanization increases the range of preferences they expect to influence. Together, they shape an employee base with greater agency and a tighter connection between what’s happening inside and outside the company. As talent is the building block of the tech sector, we need to critically consider how we manage this new quality of “human resource.”

POLITICAL TSUNAMIS

Narrow Misses: Missing factors avoid crisis

There were external political challenges in tech before 2020, but none rose to the level of organizational crisis felt since then. In 2015, Salesforce boycotted Indiana, where it had significant offices, over a state bill restricting the rights of same-sex couples. But this move was popular with employees and founder-led, pitting Marc Benioff against then-Governor Mike Pence. Right-wing news outlets had decried that tech companies were dominated by liberal employees, who shaped policy and crowded out small conservative minorities, but this was largely ignored across firms and gained no traction. However, the election of Donald Trump in 2016 amplified the political focus in society and tech companies themselves.

“Months before the election, there were reports of greater political tension in offices than in previous election cycles. In one survey from the American Psychological Association, 10 percent of respondents said that political discussions at work led to stress, feeling cynical, difficulty finishing work, lower work quality, and diminished productivity. Now, a new survey commissioned by BetterWorks… found that

87 percent of them read political social media posts during the day,

and nearly 50 percent reported seeing a political conversation turning into an argument in the workplace.

Twenty-nine percent of respondents say they’ve been less productive since the election….

With all the political posts, it seemed like people were getting worked up, argumentative, and distracted,"

The Atlantic, February 2017

In 2018, the #MeToo movement emerged, leading to widespread protests and calls for accountability around issues of sexual assault and misogyny. Twenty-thousand Googlers walked out to protest the company’s handling of sexual harassment and leadership accountability. Despite leading to important norm, policy, and leadership changes in the tech sector, #MeToo avoided becoming a political crisis by maintaining non-partisan support and having its cause already baked into the values and procedures of tech firms.

The rise of COVID-19, though at first non-partisan, also influenced the political climate within the tech sector. The pandemic heightened anxiety levels and increased sensitivity to leadership decisions as employees scrutinized how their companies handled the crisis. Lockdowns and social distancing measures cut off employees' external social interactions. Videoconferencing replaced physical workspaces and community gatherings, creating a fatiguing and depersonalized mode of interaction.

Perfect Wave: Confluence of factors builds crisis

In May 2020, Black Lives Matter (BLM) began the first of three political shockwaves that reverberated across society and into tech firms. BLM had support from a rare supermajority of Americans (67%), and within tech firms, nearly 9/10 employees supported the movement in protesting police violence against Black Americans. The BLM platform integrated into the left-wing policy platforms and institutions but had broad bipartisan support and a near-universal cultural moment after the murder of George Floyd. The movement’s core policy focused on dismantling power structures to reduce legal, economic, and representational racial inequities. In contrast, tech companies had a lower representation of Black employees and even fewer Black leaders. In addition to having large groups of progressive activists and a massive majority of employees in support, the conditions for political crises were built.

Americans are talking to family and friends about race and racial equality: 69%, including majorities across racial and ethnic groups, say they have done so in the last month. And 37% of those who use social networking sites say they have posted or shared content related to race or racial equality on these sites during this period.

Pew Research, June 2020

The Russo-Ukraine war brought a second shockwave but was initially even more bipartisan in Western societies. The cultural unity to support Ukraine and Ukrainians abroad led to immediate actions for divestiture for Russia, immigration of Ukrainian and Russian talent, and support for Ukrainian employees. For most tech firms, the crisis had a low impact and followed the standard playbook that had now emerged. The level of internal political discourse increased, requiring an external statement and support for Ukrainian employees. However, it was the most significant possible political crisis for Ukrainian and Russian start-ups and Ukrainian and Russian employees. For Ukrainians who were conscripted, under attack, and/or with family members in danger- the politicization was absolute and drove advocacy in social media and within tech firms.

The final political shockwave in the trio was the Israel-Gaza war. In the week following the Oct 7 massacre and kidnapping, Israel had similar levels of public support to #BLM. The standard crisis playbook within companies was activated and accelerated by the employees who supported Israel, winning strong representation in leadership teams of many US tech companies. For Israeli start-ups, the politicization was near universal, although national programs enabled the continuation of the tech sector despite worker and funding shortages. As the death toll from the Gaza bombings rose, a rift occurred between left-wing activists and the Israeli-supportive group in tech firms. This corporate rift was widened by the rise of right-wing activism in media and universities and the cultural swing towards Palestinian sympathies as their suffering was magnified.

These three shockwaves created historic, political waves that broke across tech firms, creating crises in many. As has been recurrent in modern history, the Arab-Israeli crisis has absorbed all the energy for political change. One might assume that this third shockwave ends the phase. However, with Trump a favorite in the polls, the old traumas and tensions will likely reawaken, and a new period of political crises could begin.

A TSUNAMI WARNING SYSTEM

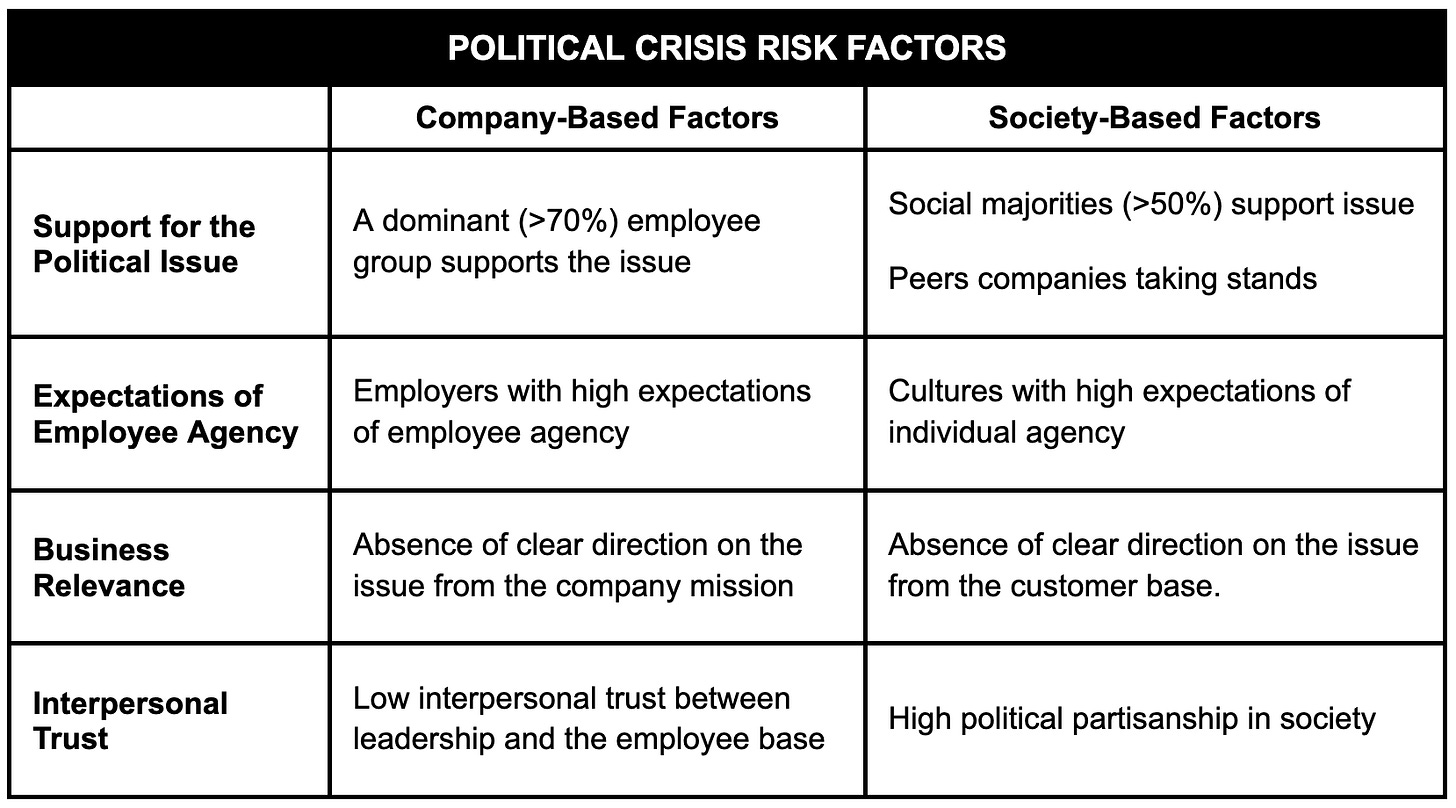

As shown above, not all significant political events create crises for companies and even those that do affect only a portion. So, how can we predict whether a political wave will break into a crisis in a tech company?

Support for the political issue

The level of support for the political issue is the height of the waves. This determines how much pressure the event places on a company. Social majorities create mainstream news and social media pressure to react. Internal majorities create dominant group dynamics by asserting norms around political issues and empowering activists. The more other trusted companies take public action to support an issue, the greater the pressure on their peers to act. No matter how firm a company is against taking a stance on an issue, there is an amount of social, employee, and peer pressure that will make a company change. War in societies of the majority of the employees creates an example of total support.

Expectations of employee agency

Expectations of employee agency are the level of exposure to the ocean. This determines how open the company is to replicating external activist dynamics. The company’s expectations of employee agency, shaped by Agile and Workplace Humanization as described earlier, are reinforced by social expectations for individual agency. In cultures with low social expectations of agency, internal activism is restricted as hierarchies are empowered. In companies with low employer expectations of agency, norms against activism are powerfully restricting.

Business relevance

Business relevance is the presence of seawalls and defenses. It provides a bulwark to deflect potential crises and empower leadership responses. Companies with a core business or critical customer segments that oppose the issue create a countering force, making it easier to deflect or ignore the political wave. Defense tech firms, like Anduril, can select employees who want to advance US military superiority rather than protest the war. However, just having a strong industry or geographic customer base that is opposed is a sufficient counterbalance, i.e., selling to the US government or Middle-East headquartered firms.

Interpersonal trust

Trust is the strength of the infrastructure. This determines the level of interpersonal resilience in the face of pressure. Good intention is more easily assumed in companies with higher trust, and division doesn’t take root. As social trust is easy at an early scale, this is why many companies smaller than two to three hundred people don’t experience political crises. In societies with higher political polarization, activist dynamics are more likely to be copied from society into organizations. Political crises can reduce trust and lower the threshold needed for subsequent political crises.

Looking at trends, we can expect further political crises in firms whose operations and business models enable it.

Social issues: Increasing populism, economic recession, AI labor replacement, and climate catastrophe could all be further triggers for political crises.

Dominant group dynamics: Globalization is likely to lessen the partisan breakdown of tech companies slightly, but the West Coast/NYC culture will still create dominant support for their progressive causes.

Rise of agency: Expectations of agency will continue to rise as Agile within organizations and generational trends towards Workplace Humanization continue.

Lowered trust: Polarization continues to be strong in the West. As I will explain, these waves of political crises have diminished trust within organizations, making further crises more likely.

MECHANICS OF POLITICAL CRISES

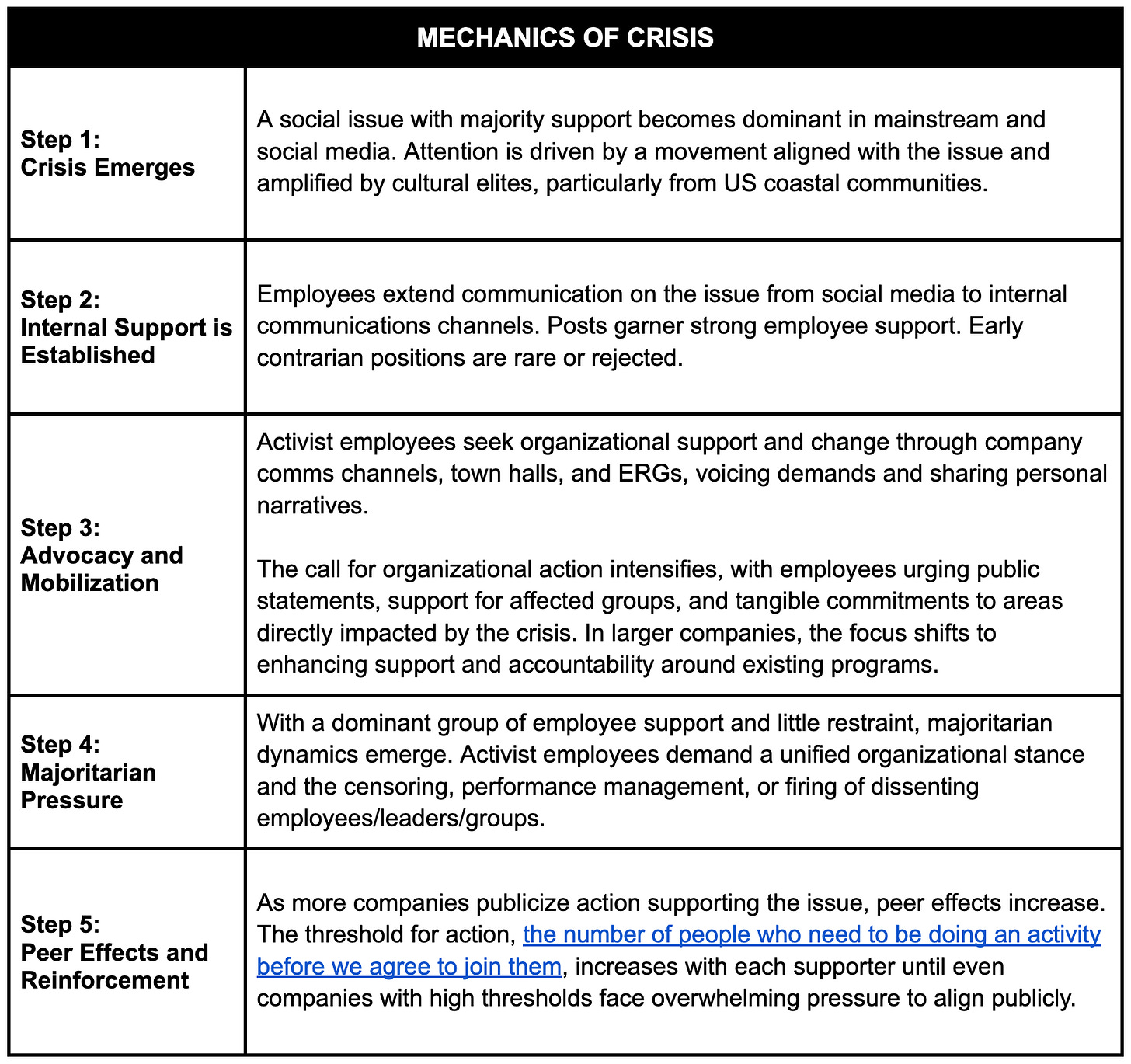

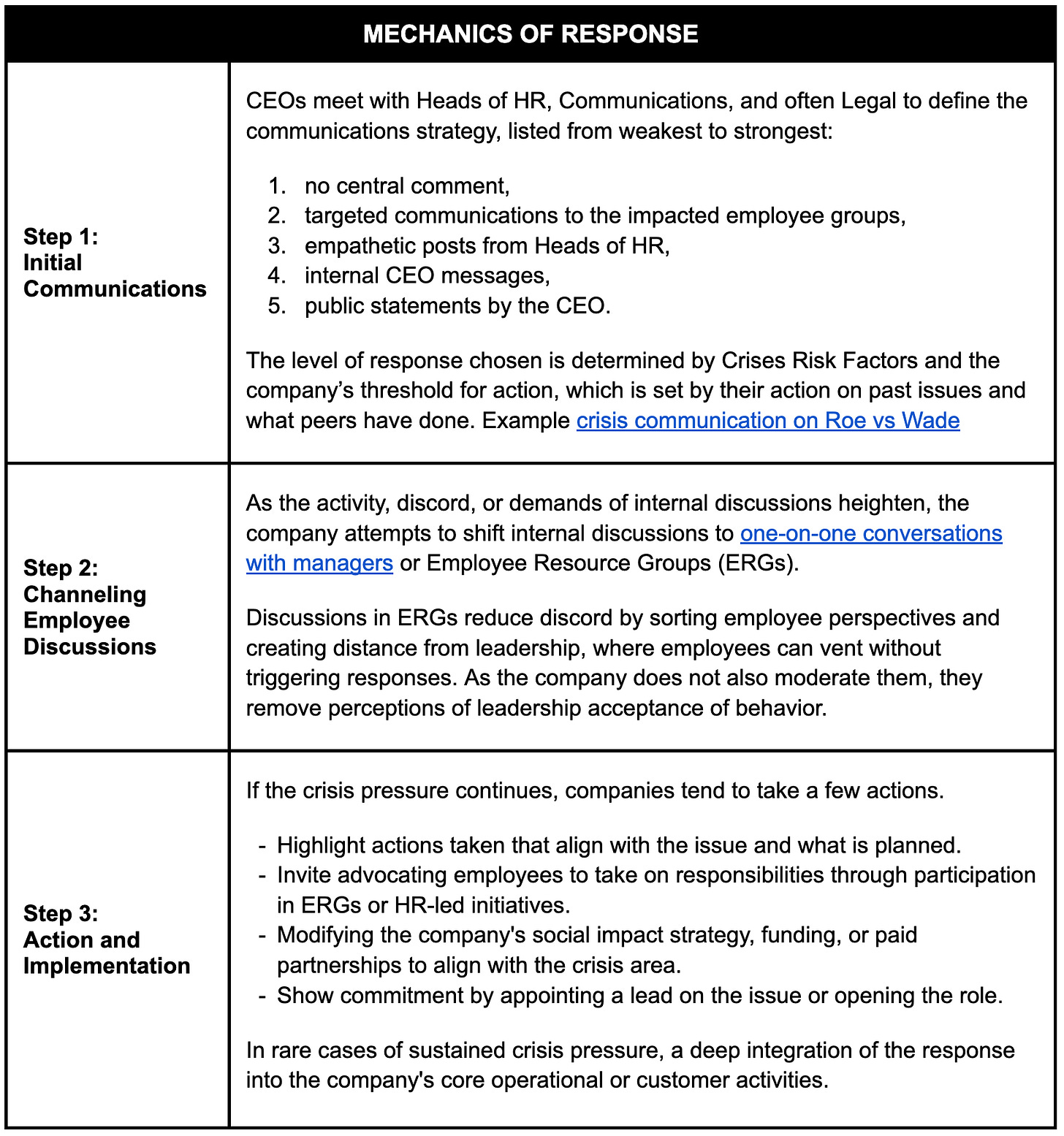

When a crisis unfolds, its progression often appears unpredictable and unprecedented, contributing to heightened tension and prompting a constrained response from the organization. However, after observing numerous cycles of such crises, we can delineate their mechanics into a structured process. This understanding enables us to grasp the dynamics of these intense events more clearly and allows a strategic response rather than a reactionary one.

Contemporary partisan activism on both sides seeks to silence opposition and hold those in power publicly accountable. Progressive activists are also more anti-capitalist and interested in inverting power dynamics. Company leaders often sense that these behaviors contradict operational norms and respond to the perceived threat with risk management and compliance approaches.

IMPACT OF CURRENT PRACTICE

The current crisis and response mechanics undermine some of tech firms' most cherished attributes: their sense of trust, unity, and speed.

The trust deficit between workers and organizations isn’t personal. It’s systemic… 80% of employees who have high levels of trust in their employers feel motivated to work, versus less than 30% of those who don’t. But less than half of workers say they trust their employer.

Deloitte Insights, December 2023

Organizational Trust is based on perceptions of competency, alignment to shared goals, and behavior based on shared norms. Activist employee behaviors challenge the leaders’ and dissenting employees' perceptions that activist employees are aligned with company goals and behaving according to shared norms. On the other hand, activists and supporting employees don’t feel that leaders are aligned (with what they see as the company's broader responsibilities) or competent in delivering on the changes they agree to. It’s noteworthy that all parties feel that implicit operating norms were violated. As described above, this lowered trust reduces the organization’s resilience against the next political crisis.

“In today’s climate, people are saying, ‘I can’t work with you if you don’t share my views.’ It’s a problem HR professionals and business leaders cannot ignore… A quarter of U.S. workers (24 percent) have personally experienced political affiliation bias… compared to 12 percent of U.S. workers in 2019.”

SHRM Research, October 2022

For decades, tech firms have stood out with a strong sense of unity, often represented in the idea of “one team.” Majoritarian dynamics mean that the politically dominant group attempts to exclude non-supportive minorities from influence in the form of barriers to collaboration or censorship. Non-supportive minorities feel silenced, unrepresented, and excluded from the organization, inherently decreasing their sense of belonging. As the political crises are formed on “wedge issues,” this group of excluded minorities is expanding.

“One of the biggest advantages that start ups have is execution speed, and you have to have this relentless operating rhythm… If you ever take your foot off the gas pedal, things will spiral out of control, snowball downwards.”

Sam Altman, How to Start a Startup

In addition to damaging culture and relationships, a political crisis significantly impacts overall momentum. It consumes the time and emotional energy of employees, managers, and executives. The level of engagement invested is comparable to responding to a new threat by a competitor. It can take months to return to pre-crisis organizational speed.

On the other hand, the current mechanics have also resulted in some changes that contribute towards their movement’s aims. BLM has more firmly rooted norms for hiring and equitable treatment of underrepresented groups. Support for the Ukrainian diaspora across Europe has been significant. Israel mobilized talent and capital to sustain its tech sector. Given the considerable costs to the employees, cultures, and business operations, we must wonder if there could be a better way to manage crises and evolve our organizations.

IN THE NEXT EDITION

In mapping out the problem in detail over this edition, I hope it’s clear why it is hard and worth solving. So far, we’ve reviewed the social currents that led to our phase of political crises in tech firms, shared a model for predicting whether a crisis will break out in any particular company and culture, and demonstrated the limitations of our current practice for managing crises. The long arc of social trends and our near view on political events show that this problem isn’t going away. The following edition will propose the “Cultural Constitution” as a new solution, drawing lessons from the foundations of political theory. I will share examples of Constitutions for a spectrum of political orientations.

Model 1: The Bay Area Standard

Model 2: The Politics of No-Politics

Model 3: A Progressive Experiment

Model 4: A Classical Experiment

I hope you’ll join me in the next edition, which will be published in June. Thank you for reading!