Designing organizations to survive and thrive in crisis

HPP#3: How a Community Constitution builds resilient companies

Apolitical Summer

Much has happened since I published the last piece on social crises in the workplace. The cultural loggerheads of Israel-Gaza have continued to paralyze political action within companies, even as the Security Council moves to end the war. Google fired 50 protesting employees, who then filed suit with the National Labor Relations Board for suppressing their rights. Meta removed Workplace posts from employees voicing support for people in Gaza. And Harvard announced it would no longer make public statements on issues that don’t immediately affect the “university’s core function.”

The previous edition, When political issues bleed into the workplace, detailed the impact of corporate crises, showing the failure of organizations to keep up with the long-term social and organizational trends toward employee agency. These trends suggest that when the organizational stalemate of Israel-Palestine is superseded by an issue that has the support of a strong majority of employees, the pressure of political crises will return. Companies with high Political Risk-Factors (support for the issue, cultural expectations of employee agency, relevance of issue to to mission or key customers, limited interpersonal trust) are highly susceptible. During this apolitical summer, they would be wise to evolve their governance approaches so they can maintain the trust, unity, and speed that are the lifeblood of technology firms.

Managing social crises in the workplace has proved extremely difficult, as it confronts a mix of ethical and identity issues, implicit norms, and leadership roles. The tensions also reinforced blind spots in how tech leaders view their organizations. We did not recognize the new qualities in our employee base and the group dynamics that were already rising before the crises. Similarly, we were unable to see solutions that would positively leverage these new dynamics. Instead, companies doubled down on their risk management toolkit and tightened management control a few notches. As a result, we missed some valuable lessons for tech company governance.

This piece will engage the problem more broadly, asking the questions:

how could we rethink our model of the organization in light of what we learned during the crises,

what new governance structures are needed to leverage these new modalities and avoid crises, and

how can these structures be applied to a range of different corporate political preferences: moderate, “non-political,” and progressive?

We need new experiments that bridge the simplistic in-group, out-group binaries of our moralistic age. I hope this piece and the associated projects contribute to this urgent agenda. With Trump already contesting the legitimacy of the ‘24 election and progressives remobilizing after his felony conviction, the next political tsunami could arrive sooner than we expect.

Machine > Organism > Community

The organizational model has evolved over the last hundred years, marking a radical increase in individual agency. The first transition, which spanned much of the 20th century, moved the model from Company as Machine to Company as Organism. The Internet Era triggered the second transition, which continues to the present day, to Company as Community.

What’s different about Company as Community?

The Community model's building block is the high-agency employee, a product of the long-term organizational social trends described earlier. This employee is highly empowered and autonomous in their work, resists narrow normative expectations, and expects to more fully integrate their personal preferences and identities into their professional lives. They seek greater alignment between their and the company’s values, including its impact beyond the workplace. This is most clear in Progressive cultures, but the same trends exist among companies seeking to attract a more Conservative talent pool- just targeting different values.

The Community model highlights that individuals bring diverse perspectives and purposes that show up in group dynamics. The alignment and fragmentation of these groups within the community bring attention to the influence of shared norms and goals, the distribution of power and decision-making, and how groups in the majority treat minority perspectives. These group dynamics can create highly cohesive, efficient, and directed companies that are resilient to external pressures or ones that are divided by conflict and paralysis. The model diagnoses both the problem and underlying causes of these political crises, showing blindspots in the previous Company as Organism model.

When can the Company as Community model be most useful?

When you need resilience. Hypergrowth has compensated for many weakly held communities. Still, every company needs a second act, and the strength of the community will determine how engaged, retained, and directed your team is after growth slows, a competitor takes a punch, leadership changes, or a crisis hits.

When you need the next generation. High-agency individuals demand community for fulfillment and productivity. But if unmediated by appropriate structures, they can breed misdirection and mistrust, disrupting economic and cultural progress. A swing back to command-and-control approaches that have often followed only exacerbates the problem and reduces the company's ability to leverage the next generation of business and talent.

When you have a broken community. If there is a major division in the company a community model can help reset and rebuild. It helps us make clear the implicit norms, purpose and relationships that are at the core of our organizational strategy. A broken community is not solvable with employee engagement processes in the same way that product development can’t be addressed in customer surveys.

Start-up Archipelago

So, how do we build communities that cultivate and align high-agency individuals to create excellent business and cultural outcomes? Western democracies, where the culture of agency is most advanced, are too scaled and institutionally complex to serve as an effective model. Companies are smaller, simpler, and far less democratic. They would be single-party states, with power concentrated in either a managerial class or even a single executive. Rather than contemporary society, we can find a closer analogy by going back into our history to a moment when social structures were smaller, democracy was just emerging, and the political community was first being conceptualized.

There were around 1500 independent city-states competing in the Ancient Greek world, with citizens numbered in the high hundreds to low tens of thousands. It was a structure much more similar in scale to a start-up ecosystem. These communities had a broad spectrum of governance models, citizenry rights, and economic policies, but most were consolidated monarchies or ruled by an elite class. Protodemocracies, like Athens, were few, and their simple systems were as prone to mob rule as authoritarian states were to tyranny.

Against this diverse political laboratory, Aristotle wrote the first empirical evaluation of social organization and its progression. In Politics, he was early to identify that it is human nature to seek community for fulfillment and belonging, the cultivation of values-based action, the exertion of moral influence in the world, and as a source of stability and change. However, he also noted that community aims were far from guaranteed and that corruption and decay were possible, regardless of the power-sharing model chosen.

Aristotle's solution focused on a constitutional framework as the defining structure of the community. This was not just a framework for government but an expression of identity, values, and aims that aligned and educated the community. Given its expansive coverage of productivity and cultural factors, plus its flexibility across modes of governance, Aristotle’s framework provides a useful model for how a modern company can thrive with a high-agency employee base.

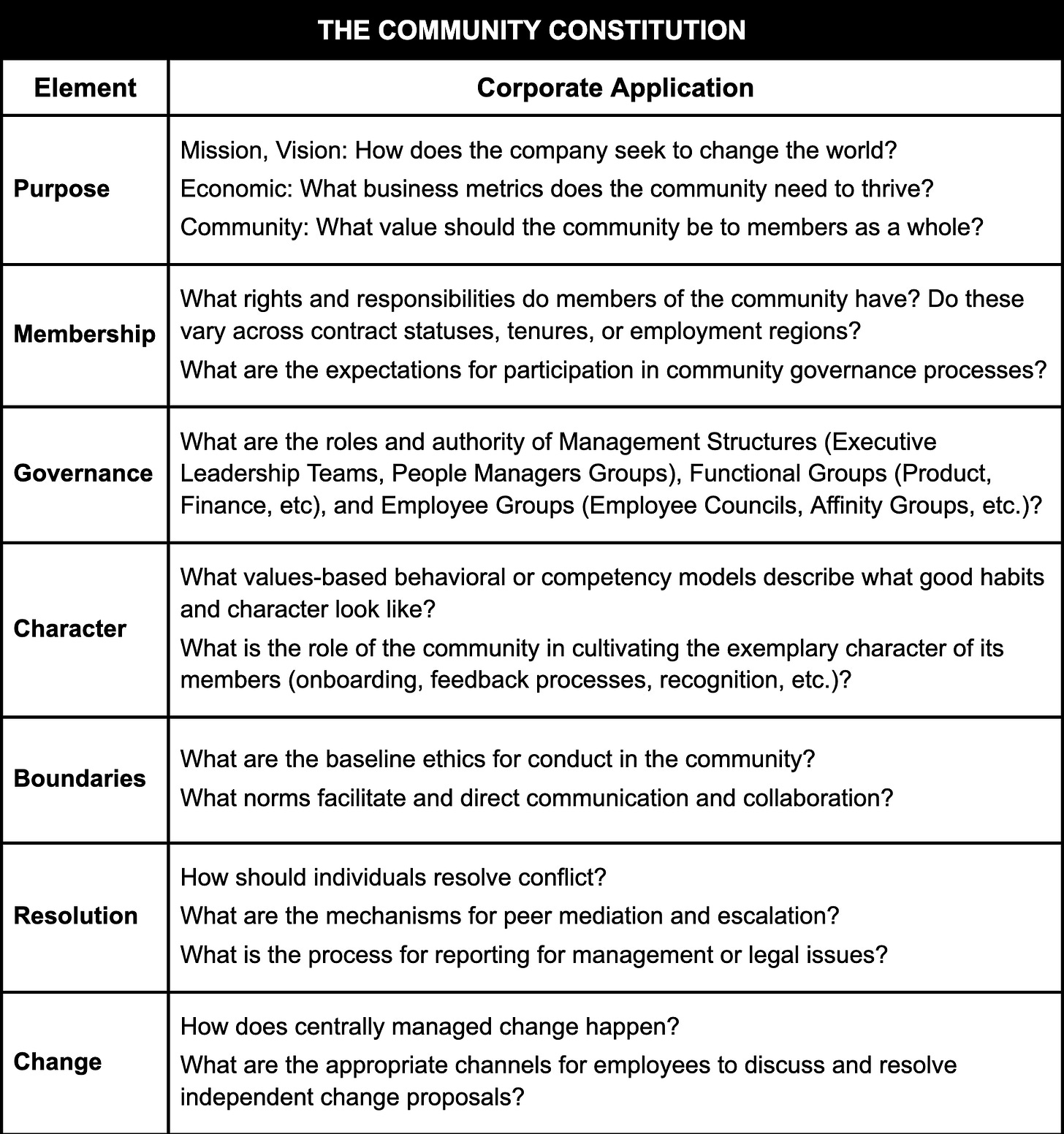

The Community Constitution

What’s different about Community Constituion?

It makes norms explicit and actionable. Often, norms around power, change, conflict, and membership are implicit and can be unknowingly broken, which raises tensions.

It specifies purposes. Social aims are often vague, which allows overinterpretation or can make action seem arbitrary. Similarly, the community's aims are rarely specified.

It elevates the community. Employee community is currently synonymous with events. A Community Constitution aligns existing cultural artifacts around greater community purposes, complements them with elements needed to thrive, and elevates it to the level of organizational strategy.

A Community Constitution is not a legal document like Articles of Incorporation, Corporate Bylaws, or an Employee Contract, yet if practiced, it is instilled with meaning and influence. At its core, it is a moral framework for the community, targeting aspirations for growth, collective benefit, and virtuous action. This makes it a powerful tool for reconciling the personal and ethical tensions and reactions at the heart of conflict and crises.

Implementing a Community Constitution

The objective of a Community Constitution is to create a thriving corporate community that fulfills its purposes, where its component elements are in active practice, and with the strong support of almost all employees. There are several steps for successfully implementing such a framework.

Customize: Draft the Constitution for the company's unique business, culture, and governance mode, making each of the component elements explicit. This makes norms more influential and updatable, reducing tensions from members unknowingly contradicting them.

Activate: All community members need to be involved in incorporating the Constitution and establishing the community. Cultural influencers and leaders will need greater buy-in. Aspirational elements must be carefully implemented, closing gaps between the explicit and implicit norms. It’s essential to induct new hires into the community so they understand the framework, their roles and responsibilities, and how to drive change appropriately.

Respond: When a crisis arises, norms should be strong enough that unconscious violations are rare and quickly resolved with remediation processes. Having set channels to address change proposals in light of the defined purposes should harness activist energy. If there are conscious and repeated violations, the framework serves as a robust cultural force to excise disqualifying members or an explicit set of norms to update and strengthen.

Putting the Constitution to Work

“...one might say that the best constitution is not simply the best in an absolute sense, but the one that is most suitable for a particular people." Politics, Book IV, Chapter 11.

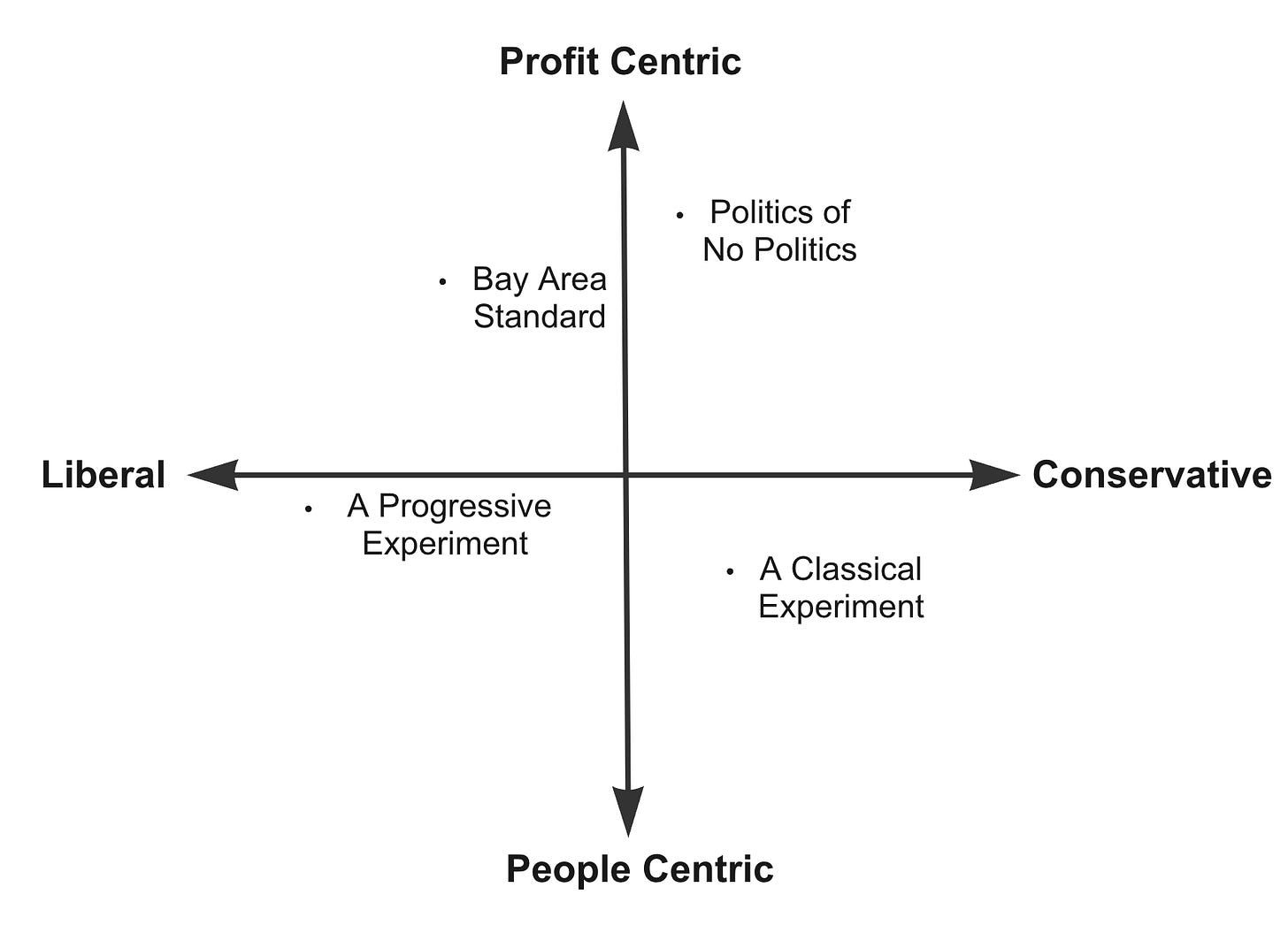

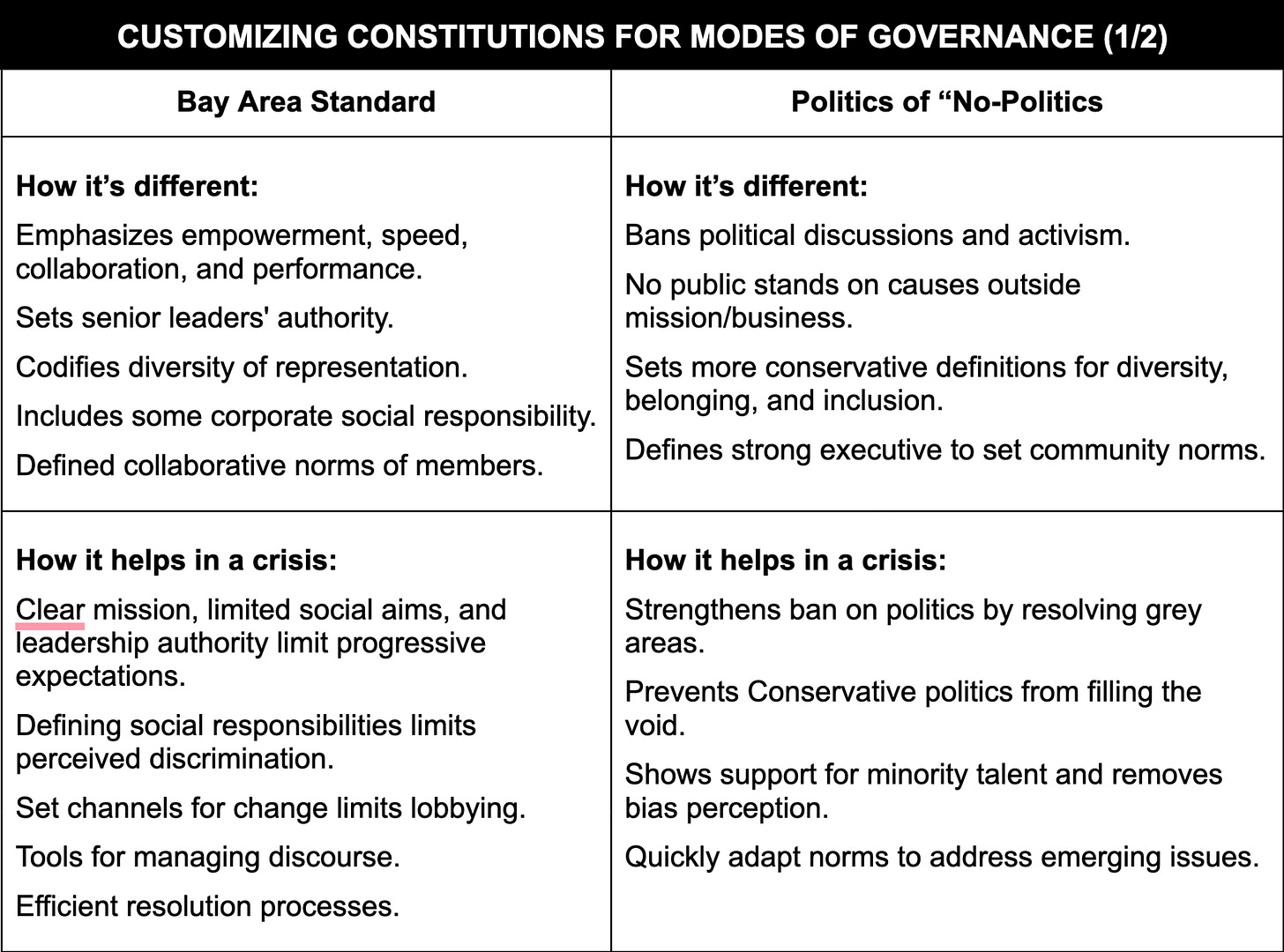

The framework of the Community Constitution gives us the flexibility to adapt to the variety of scale-up governance modes that we see now and to plan new experiments. This final section maps dominant and novel archetypes to show how Community Constitutions could differ and how each type would help weather political crises.

Model 1: Bay Area Standard: The standard set by the rise of Silicon Valley Tech Giants and globalization of coastal culture, it is defined by moderate liberal values, strong hierarchies, speed, teamwork, and a sense that they are a force for good in the world.

Model 2: Politics of “No-Politics”: This rising alternative bans political discussions at work and seeks to undo Progressive cultural features. Coinbase and Basecamp exemplify the model that positions itself as apolitical, though it most popular in Conservative verticals and employee populations.

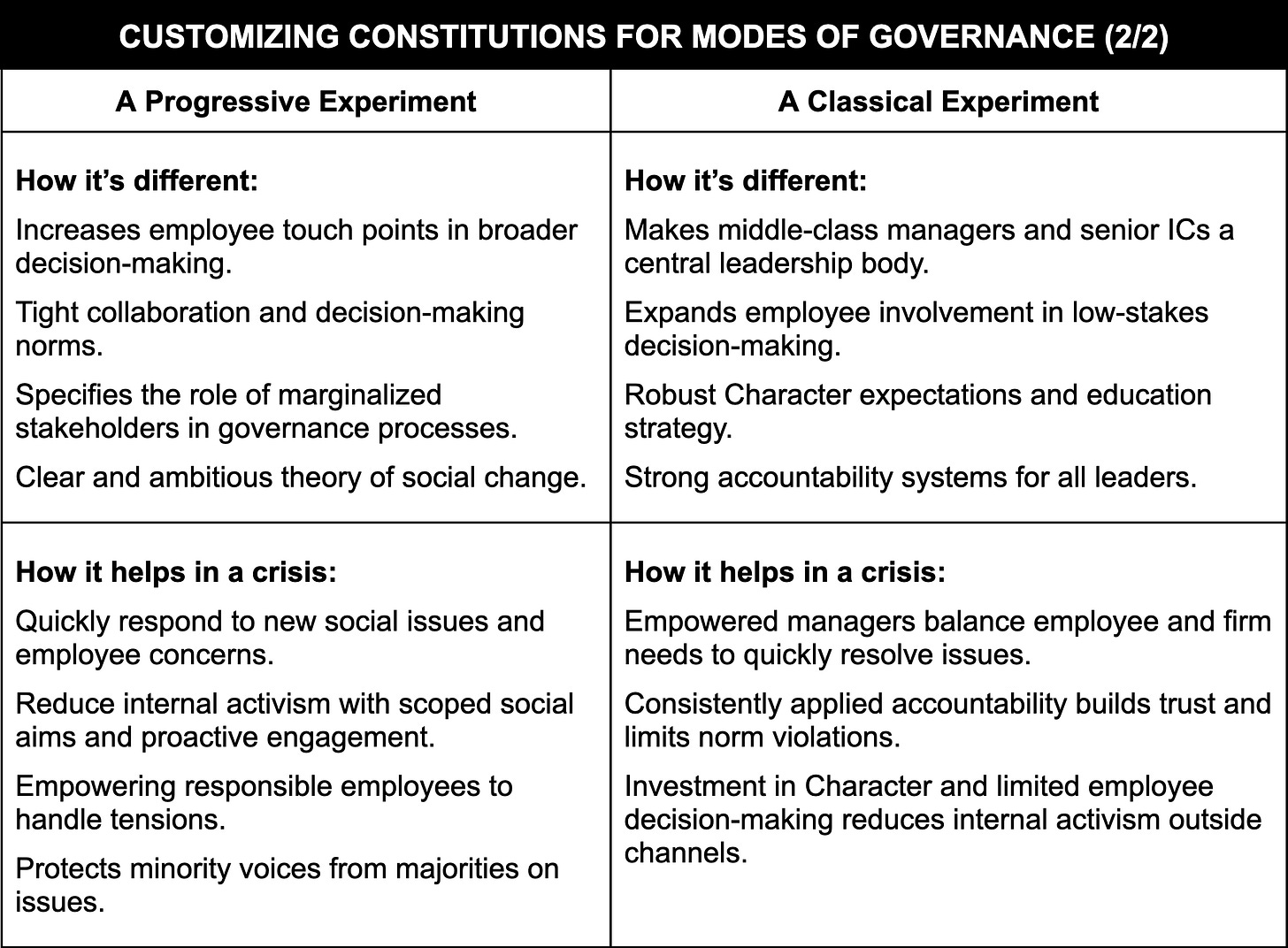

Model 3: A Progressive Experiment: This experiment tries to authentically incorporate progressive ideas of democracy and intersectionality into a fast-moving business to attract very progressive tech talent seeking alignment of values.

Model 4: A Classical Experiment: This fun experiment considers what Aristotle would suggest if his ideas of the ideal political community were updated for a modern tech business and from the barbarism of the ancient world to contemporary social values.

Governance for the Next Generation

As technology and economics help us more easily fulfill our basic needs, new generations seek greater actualization. Autonomy is motivating. Feeling resonant with the values you are immersed in is motivating. Yet, unmediated autonomy, which was well-inspired to close perceived values gaps, has led to political crises within organizations. We face a choice to swing back towards less empowering models of the organization or to advance with governance structures that can match the emerging ethos.

Community is the platform upon which the high-agency talent pool can be engaged, connected, and aligned. Properly guided, a community can demonstrate resilience and change in the face of inevitable crises. Customizing a Community Constitution to the unique mission, implicit cultural norms, and economic realities provides a practical and moral framework for the company. It offers a path to business resilience and collective thriving, avoiding the pitfalls of majoritarianism and authoritarian leadership. And with the pressures of political partisanship and the transformations of AI, we will need a lot more resilience.

Thank you for reading! I would love to hear your thoughts. Feel free to reach out below, by email or on LinkedIn. Hard People Problems is a deep dive into the toughest problems in HR, delivered free every two months. Subscribe to stay in the loop and support my work.